Teresa had an assignment to write a horror story recently for Language Arts. I don’t think I ever had that assignment, but it sounded like fun.

On a Spring day it’s easy to get fresh strawberries. Every store has them, overflowing from their swishy doors out into the parking lot in cornucopias of rustic wooden platforms covered in 2 for $3! signs.

But in the late Fall or early Winter? You need is to get there early. And be ready to pay.

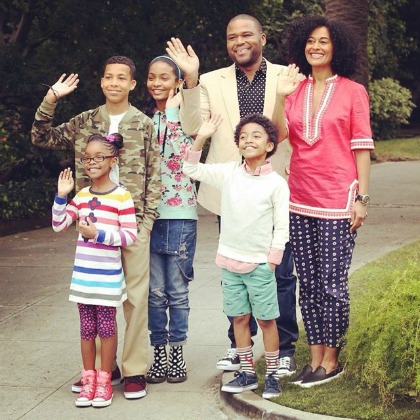

My daughters love strawberries. As long as there are strawberries in the refrigerator, there are no fights. Chores and homework get done. Memes are happily shared around the kitchen table.

Wednesday night. The weekend’s berries have been happily consumed, and even if they hadn’t been, they wouldn’t be good anymore.

I set my alarm for 5:30 and go to sleep confident. Beep beep beep. Some people configure their alarms to be music. But no matter how great the song, if it’s an alarm, you’re going to end up hating it. But there’s no love lost on beeps. Like smashing a mosquito, I dismiss my alarm with no hard feelings.

I wake up. My phone says 6:56 am. Oh no!

The peace-creating strawberries rot in my mind and tumble into the kitchen garbage. “Hey, these dishes are dirty. Who washed them?” Verbal sparring begins. I know it will lead to a day or more of hard feelings, followed by a weekend of grousing.

Jump out of bed. Pants. Sweatshirt. No time for underwear. Wallet.

Keys? Where are they? Oh, on the floor. Nope, that’s my bike key. Okay, we’ll go with that. No, I’ll never have time if I try to bike to the store.

7:01. To the store and back by 7:30 or else I’ll miss the breakfast window. Keys, keys. Bathroom? No. Gotta pee. Keys. Okay, where else? Kitchen counter? No. Coat pocket? No, no.

In the garage, still no car keys. In the car? What, it’s locked? Squint through the window. No. Wait, there they are! On the passenger seat! No, that’s the set with the dog keychain. No telling where mine are.

7:04. Still in the garage. Have to bike. 10 minutes there, 10 back, allows 6 minutes for shopping. Possible. Maybe if I pedal fast.

The garage door rises, a mouth of darkness. As soon as it reaches head level, head out into twilight.

Whoa, frost! Augh! Slippery! Foot down! Relief and frustration rush through me.

Blinding light. Whoosh as a car rushes by. I follow it out onto the road.

Pedal madly and look in every direction at once. Merge with traffic. An antelope among lions and elephants.

Red hatchback ahead, dark SUV behind.

Red light. Exhaust fumes. The driver in the next lane gives a sideways glance. Resting face, or incensed?

Green light. An engine races behind me. My legs pump. Don’t look back. I can keep up with this traffic. Shift. Shift. Shift.

Brake light! Skiiiiid. Catch myself against Red Hatchback. Scraaape of bike frame against car

Something hot on my shin.

Inside Red Hatchback, the rearview mirror frames the driver’s alarmed eyes and mouth open in an “Oh”.

I’m still standing. Back up, wave hands to say “never mind I just need strawberries”.

Everyone is turning left into the grocery store lot. Pumpkins. Haybales. 20 cents off gas with card. Pour gas onto the haybales, but that would make it harder to reach the strawberries.

But I’m still in the road, standing over my bike frame in the left turn lane.

Someone ahead in line is being too cautious. There is a chance to cross the other lane.

Go! Jump the line! Pounce on pedals to get in front of a slow truck.

The pedals don’t move! Broken!

No, accidentally in high gear! Bike is moving so slowly. Oncoming truck is slowing down. The opposite curb is coming closer, closer.

Hooonnk

Foot down on curb, lift, pull bike out of road.

Whooosh. Angry yelling. My face is red.

Remember the strawberries.

The bike rack is at the far door. I’ll leave my bike propped by this door. No time to lock it.

A huge bin of pumpkins. Orange and useless.

Through the swishy doors. Apples. Pears. Peaches!? Blueberries.

Pumpkins. Bananas.

“Oh my gosh, is your leg okay?”

What? It still feels hot, but cold too. Oh, that’s a lot of blood.

“Yeah, it’s fine. Have you seen any strawberries?”

“Oh, honey. I’ve got some bandaids in my purse.”

“I’ll take care of it when I get home. Excuse me, sir, yes? Do you have any strawberries?”

“Well, I’m putting out the fresh stuff now. I think maybe some came in last night, but we don’t have any out yet. Oh, here are some.”

The rejects. Maybe there are some good ones in there, at the bottom.

“Thanks.”

I take both remaining packs.

7:14. Ahead of schedule.

Self check-out. Please …. place …. your ….

Please …. wait …. for …. an (No, not an attendant) …. attendant

7:17. Where’s my bike? Someone riding it away through the parking lot?

Wrong door. It’s still over there where I left it, behind a cart. Running.

Strawberry cartons in plastic bags, swinging from the handlebars.

Going back is so much harder. Is it uphill? Barely. Push through.

Look behind: A car too close. Ahead: so much distance to cover—I try to catch up, pump hard, but my legs can’t compete with internal combustion. The driver’s stare weighs on my back.

I hop a driveway lip to get off the street, my slow motion too antiquated for the motorized commuters.

Imagine the strawberries on the kitchen table. In time for the day to start. Hands reach in, pluck from the carton, pop them into mouths that are smiling and talking. A team huddle, all hands in for a cheer. Everyone’s making plans for the day. All is possible.

The frost is gone, leaving damp sidewalks. Almost there, but I still have to cross the street. I should have done it at the crosswalk. Maybe I should go back? Or go up to the stop sign? Suddenly sleepy.

Where did all these cars come from? It’s not time for the rush yet, is it? There’s a break. But not on the other side. Have to wait.

Finally back in the garage. Kickstand.

Inside door to the house is still open.

In the kitchen, munching teenagers, phones out, catching up on the instanet.

“I got strawberries.”